Who was Flossie?

A computer with a surprising story - and a knack for survival.

The ICT 1301 family was one of the first commercially successful, British-made business computers. Around 200 were manufactured in the 1960s and the machines sold across the UK and globally, from Poland to New Zealand. Today just four ICT 1301s remain - including Flossie here at The National Museum of Computing (TNMOC).

Flossie was first out of the ICT factory back in 1962 and assigned serial number six. She lacked an operating system, the program was loaded by hole-punched cards or magnetic tape and she weighed nearly six tons. Flossie was massive by today’s standards but was a step change in computing - putting data-processing power in the hands of more people. Having escaped the scrapheap three times in her life, she has been painstakingly restored to full working order.

Virtual Flossie is a journey around the life, times, people and places of Flossie and the ICT 1301 family - with the opportunity to try your hand using this iconic computer online.

The Virtual Flossie Experience

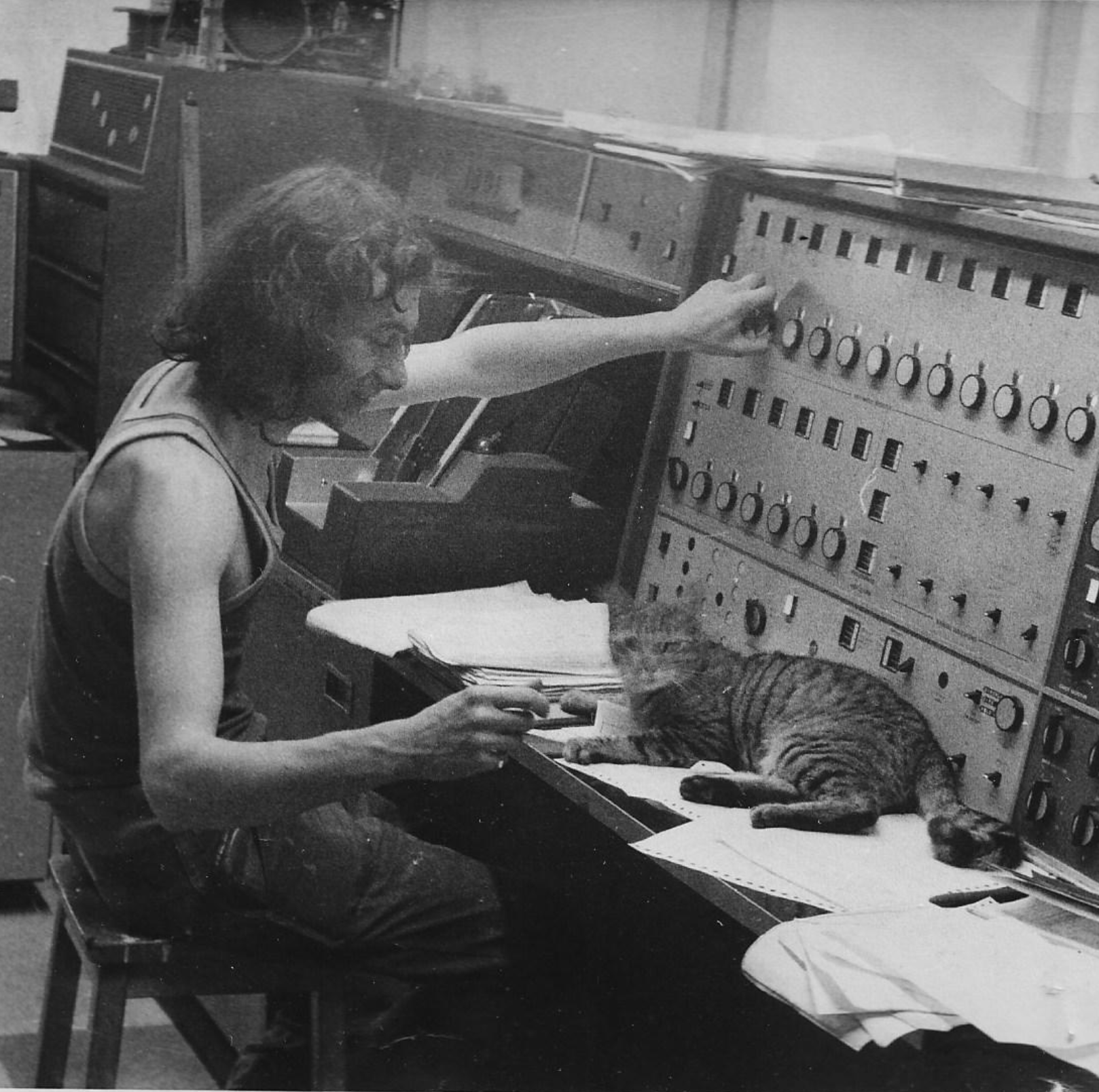

Operating Flossie was nothing like using a computer now. First you had to load your program - from punched cards or magnetic tape - then install your data. You hit buttons and altered settings on a console of dials and flashing lights. Click on the image above and follow the instructions to use TNMOC’s Virtual Flossie. You will get a taste of 1960s computing power, installing your program on virtual punched cards, operating the console and producing your program’s results on virtual and physical cards.

Future design vision

Not just a computer - and not just the 1301! Read Award-winning design eye of Noel London, below, to discover more!

Photo: The Design Council Slide Collection at Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections Museum

Students buy computer!

Graduate and go into business for £400? Discover how the first ICT 1301 escaped the scrap heap in Second life: welcome to Galdor, below.

Image courtesy of Stuart Fyfe

The talented Dr. Bird

The 1301 was his second best-selling computer. Learn more in Dr. Raymond Bird: the genius who struck twice - below.

Photo: John Robertson

Transporting a legend: Moving the first ICT 1301 from the University of London to Galdor Computing.

Photos: Stuart Fyfe and Andy Keene

-

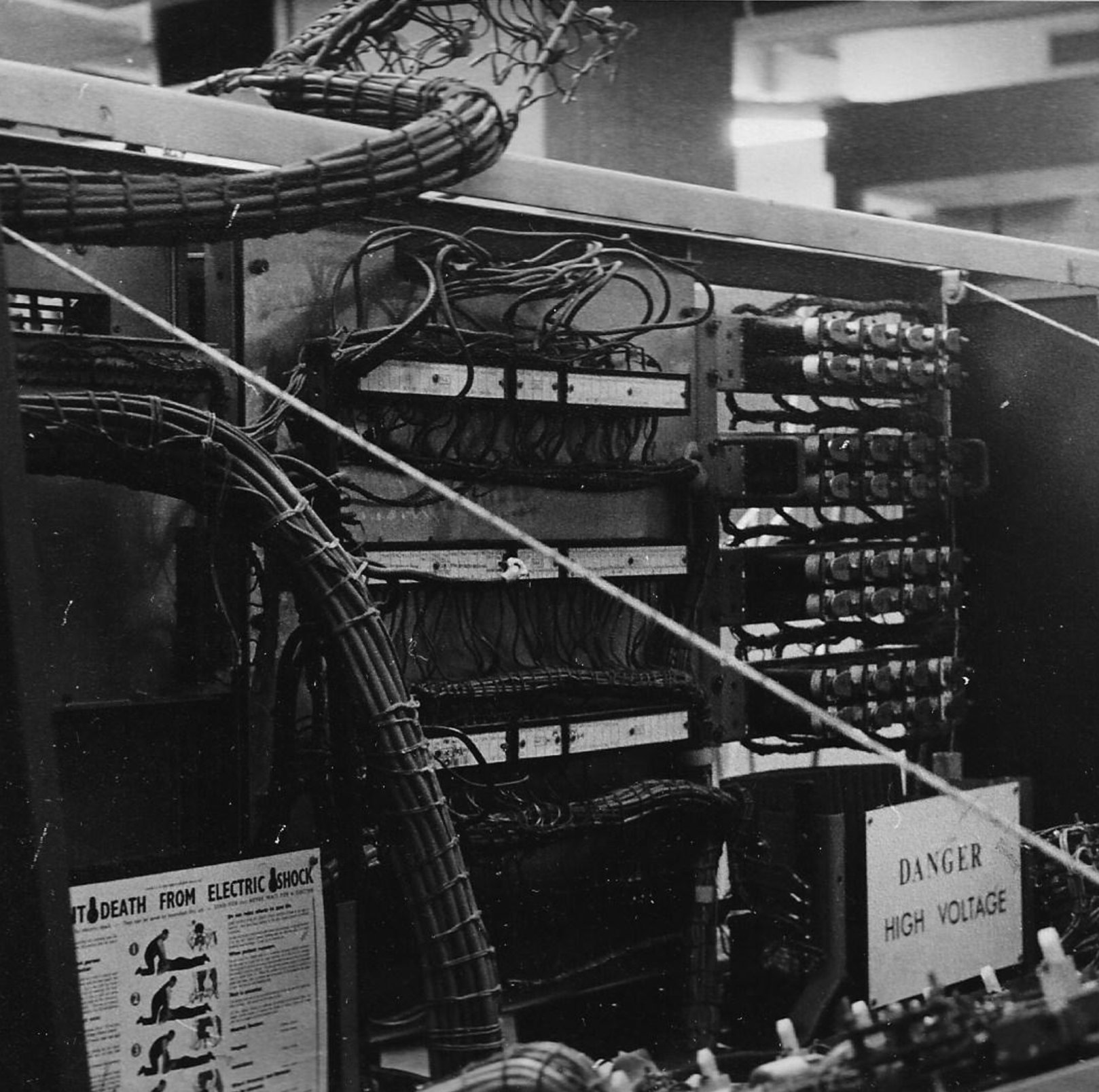

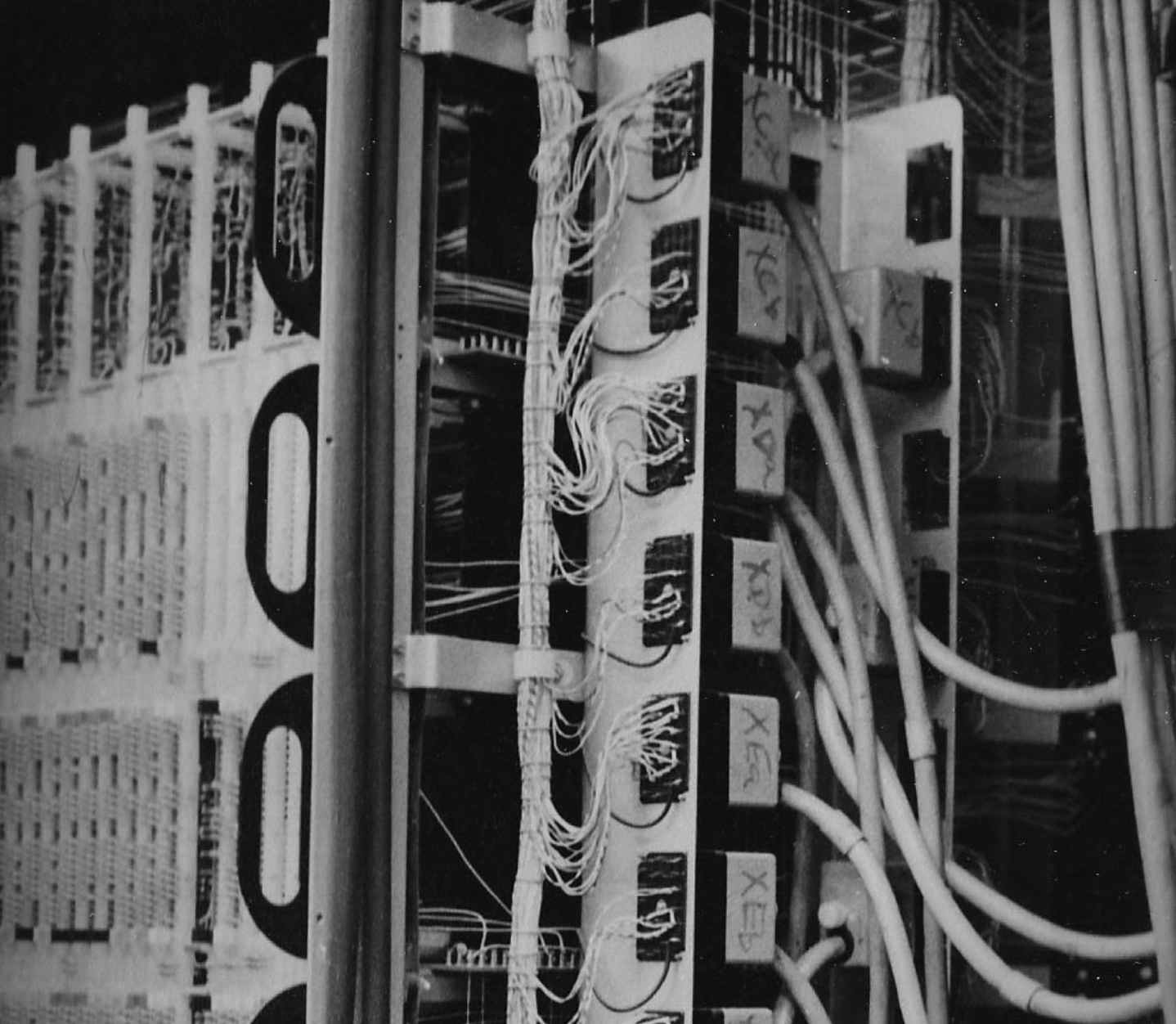

The 1301 from International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) included a number of distinguishing technologies and features that made it unique.

The use of decimal instead of binary logic made it easier to program and it featured the ability to handle pre-decimalisation currency - pounds, shillings and pence. The ICT 1301 featured a high-speed printer that was capable of 600 lines per minute so users could quickly print their data outputs and, also, no longer had to rely data output to hole-punched paper tape or cards. Storage on magnetic tape was added later for even greater capacity - up to eight metal and glass cabinets containing magnetic tape reels for further storage.

But two features made the ICT 1301 really stand out: the 1301 was ICT’s first computer to adopt germanium transistors and magnetic core memory. Both were new at the time and were stepping stones to smaller, reliable, more powerful computers produced at lower cost.

Developed in the US by Bell Laboratories in 1947, germanium transistors replaced vacuum tubes used in earlier computers. Germanium transistors were more reliable than vacuum tubes, they consumed a smaller amount of power, weren’t as fragile, and physically smaller in size. The ICT 1301 consisted of 7,352 germanium transistors on 4,000 printed circuit boards.

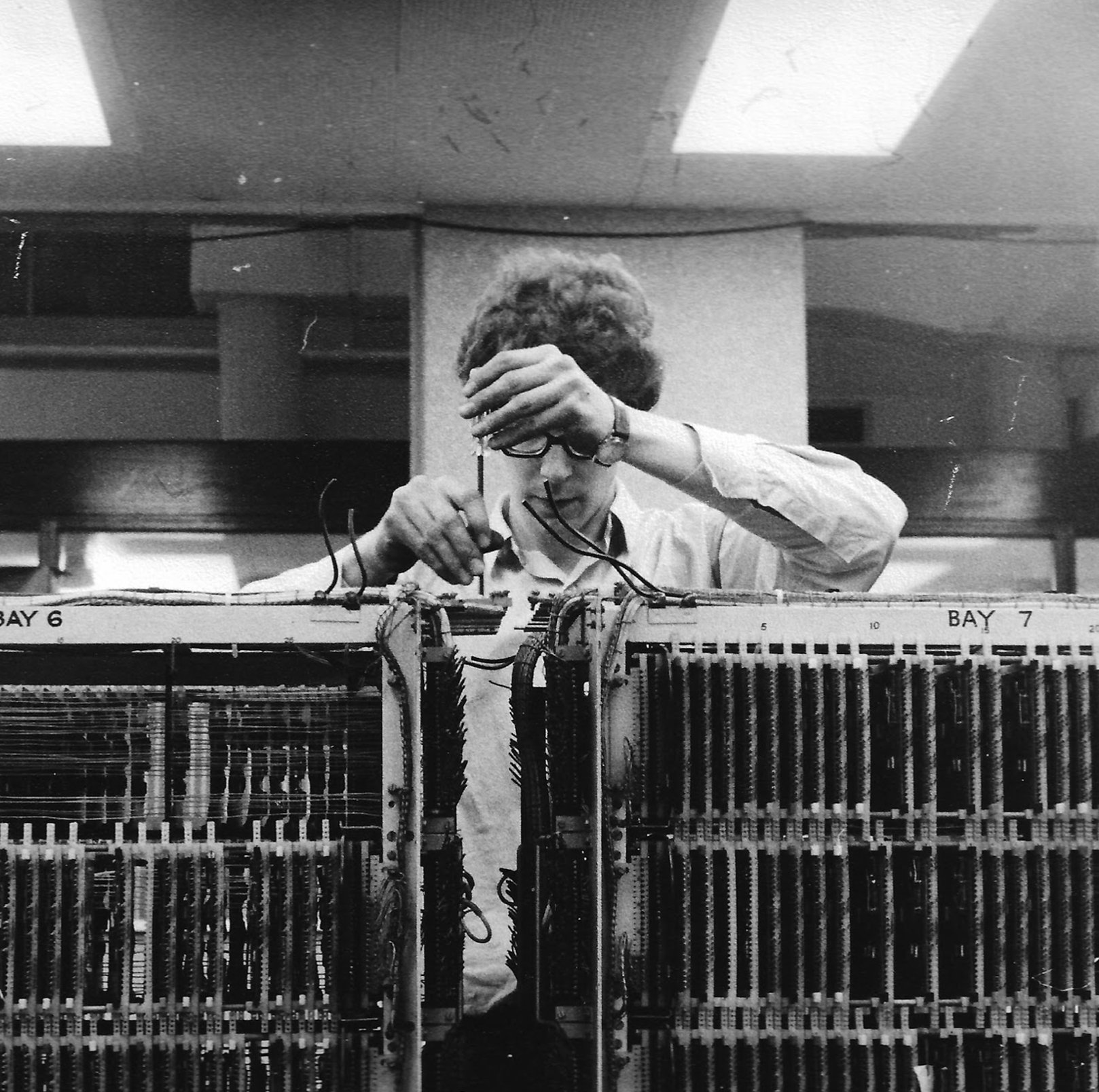

Magnetic core memory, used successfully for the first time in 1953, consisted of a mesh of tiny metal rings hand woven together and magnetised to represent zeroes and ones. ICT branded its version of magnetic core memory Immediate Access Storage, reflecting its ability to retrieve data faster than technologies like rotating drums that made it suited to larger and more complex data-query work. IAS also had greater capacity - 100,000 cores and the 1301 a main memory of up to 12,000 bytes.

-

The ICT 1301 has a corporate connection that extends to code breaking and Alan Turing at Bletchley Park during the Second World War.

The 1301 belonged to International Computers and Tabulators - ICT - but ICT came into existence in 1959, midway through the computer’s development. ICT resulted from the merger of Powers-Samas, famous for punched-card machines, and the British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) which dominated the UK and Commonwealth market for these machines.

Tabulators were electromechanical devices used widely in business and government to process and collate large amounts of data stored on punched cards. BTM’s experience meant the British Government awarded it the job of building and assembling another type of electromechanical device - the Bombe, which helped codebreakers decrypt radio messages sent by the German military encoded using Enigma. Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman are credited with the Bombe’s design. Their machine automated the process of finding patterns in encrypted messages to identify each message’s key and therefore help codebreakers crack the message.

Construction and delivery of Turing and Welchman’s creation was handled by BTM’s factories in Letchworth, Hertfordshire - the company dedicated 70 percent of its manufacturing capacity to the job. The first machines took six months to build but production ramped up to one a week once Bombes were produced in batches. Finished machines were dispatched by army lorry - with just a single soldier as escort - either to Bletchley Park 53km (33 miles) away or one of its outstations.

-

The ICT 1301 was one of the first successful British-made business computers. Dr Raymond Bird was its designer - but the 1301 wasn’t his first success.

Bird joined the British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) - which became ICT - from GEC where he'd worked on improving vacuum tubes that were used by the first generation of digital computers. BTM recognised computers were coming but was concerned by their tendency to be expensive and built for just a single purpose. Bird undertook a fact-finding mission during which he met Dr Andrew Booth of Birkbeck College in London. It was a critical moment: Booth shared his design for a computer that could be affordably produced for a big market. Bird led a team which built the prototype that became the Hollerith Electronic Computer (HEC) - now on display at TNMOC - which copied Booth’s circuitry but added extra interfaces. Bird would refine the prototype and deliver subsequent models with the HEC4, marketed as the BTM1200, becoming the biggest selling British computer of the 1950s by volume: 70 were sold.

Bird was set the task of designing the 1200’s successor and was transferred to Computer Developments Ltd, a subsidiary BTM created with GEC to complete the mission. Bird wanted to marry technical innovation and commercial capabilities but - by his own admission - the 1301 was more complicated than anything yet undertaken. It had been possible for a relatively small number of individuals to design and build the first commercial computers but BTM’s strategy for the 1301 changed this. New technologies and capabilities created complex challenges and more sophisticated subroutines - a bigger team was needed.

Software was one issue. Until now, BTM had provided customers with certain subroutines and trained them to programme their machine. The 1301 turned this on its head. The magnetic core, for example, demanded new control routines that had to be written by BTM using a large team of 20 programmers working round the clock. The 1301 introduced storage on magnetic tape that wouldn’t synchronise properly so Bird had to design a new system of error detection and correction to overcome this. ICT also had to source a reliable magnetic tape drive and a printer, both of which came from the US and entailed trips to meet the suppliers.

Ultimately, however, these challenges would be overcome and Booth’s design for the 1301 was realised, with enviable sales during its lifetime of more than 200.

-

As new and faster computers began to replace the ICT 1301s, a second life beckoned for the very first machine to go into use - the University of London’s machine.

Unable to afford computers of the time, many firms and individuals would pay for computing services. In 1973 Galdor Computing, formed by a band of friends who bought the University of London’s 1301, began selling these services operating in the back garden of their south London home.

Friends Stuart Fyfe, Trevor Jarrett, Andy Keene and Derek Odell, had originally decided to buy a second-hand computer while studying at Kingston Polytechnic. They had planned to use the computer for remote control of the Kenley Astronomical Telescope for the Croydon Astronomical Society, so scraped together £200 to buy the University’s 1301. They beat scrap-metal dealers who’d offered thousands of pounds - the University was happy to see its computer continue in the service of education.

The friends dismantled the 5.5-tonne, steel-framed machine over a period of two weeks and moved it by lorry but it was an inheritance from Andy’s great aunt Florence that finally allowed the friends to get their 1301 up and running - earning the 1301 her new name. Flossie was installed in a prefabricated house over a six-month period and Galdor soon built a base of 35 customers. This gave them the skills to take on a massive job: a six-month operation running for 24-hours a day towards the project’s end processing records and reports for Liverpool Victoria Insurance as the insurance giant switched to newer computers. Spare parts for Flossie were sourced from other 1301s as they were retired for scrap.

Galdor upgraded to an ICL 1900 in 1977 and sold Flossie - for £200.

Catch Stuart as he discuss his experiences with the 1301 in our video: Second life for an ICT 1301 called Flossie

-

BTM - which became ICT - dominated the British and Commonwealth business market for punched-card data processing but the world was changing: digital computers started to replace electro-mechanical tabulators that had been widely used to process punched cards.

BTM wanted to convert its tabulator customers to computers but faced stiff competition: EMI, English Electric, Honeywell and LEO at home while - from the US - came IBM: IBM released the world’s first commercial, germanium-transistor computer and followed up with the 1401 while the 1301 development. Nearly 100 IBM 1401s were installed in the UK between 1961 and 1962 - accounting for third of computer sales with the majority replacing tabulators from what had become ICT.

BTM had wanted an affordable, small commercial computer and decided to partner with an electronics manufacturer to deliver. It partnered with GEC in Coventry - a specialist in telecoms equipment - for its manufacturing skills, expertise in making reliable systems, an ability to quickly adapt to changes in computer memory and processor technology, and because it had not declared intention of marketing computers. The companies formed Computer Developments Limited to work on computer designs that included the 1301 but IBM’s 1401 accelerated 1301 development.

The first 1301 - serial number six, which became Flossie - was installed at the University of London in 1962. It was used to process student exams results and process administrative work.

The combination of a speed of magnetic core memory, 1MHz clock speed and parallel data transfer made the 1301 suited to complex and intensive data-processing tasks for customers.

1301s were therefore used in aircraft design work, insurance policy calculations and billing large insurance firms, calculation of local authority rates, timetabling and rolling stock calculations for the national railways, payroll for large companies and government departments. Customers included the Department for Education and Science, Metropolitan Police, British Rail Freight, John Lewis Partnership and Liverpool Victoria Insurance. The 1301 started at £100,000 for a “basic” model.

-

The ICT 1301 was good looking and practical - for that, credit goes to Noel London of the award-winning industrial design consultant London and Upjohn.

The 1301 was among a generation of computers that exchanged valves and cumbersome memory units for transistors and cores. This not only helped them become more powerful it made them smaller - albeit the ICT 1301 still occupied 65 square meters (700 square feet) of floor space - allowing them to be used in more workspaces.

It therefore became possible - and increasingly desirable - to hide the inner workings. The ICT 1301 weighed over five tonnes and was built around a steel and iron frame that ranged in thickness from a quarter to two inches. Probe inside and you risked electrocution - the back of the console contained bare electrical terminals conducting 440v AC.

Moreover, as computers left the laboratories where they’d been built and programmed, it became vital they could be understood and operated by everyday users.

Some systems were packed inside metal cases or built into desk-like structures. London and Upjohn adopted a modern, industrial chic. A control console was angled at just the right position for both standing and sitting, disciplined lanes of lights, buttons and dials were all angled and positioned within easy reach, as were the punched-card trays. All this was housed in a casing of modern polished metal and grey.

The design is credited to London with the console winning recognition by the British Design Council which was working to promote excellence in British manufacturing. The ICT 1301 would receive the Council’s black and white triangle tag that recipients could use in advertising and marketing to help promote the quality of their design.

The 1301 appears to have been the start of a rewarding partnership between ICT - which became ICL in 1968 - and London and Upjohn. The consultancy worked on the 1900 which succeeded the 1301, with the 1904A model earning a Council of Industrial Design award in 1970 and the ICL 2904 a Design Council Award in 1977.

The work of London and Upjohn spanned the decades. From telephones for the General Post Office to fork-lift trucks, their minimalist and functionally efficient work would receive further recognition from the Design Council in 1980.

Hear from Stuart Fyfe on saving the first ICT 1301 from scrap dealers and building a successful back-garden computer services business with friends at their 1970s' South London flat.

Why was the ICT 1301 a commercial hit? ICT and ICL customer support engineer Rod Brown discusses its business appeal - and biggest customers.

Dame Stephanie Shirley: building and testing the ICT 1301 for Britain

Dame Stephanie Shirley is a renowned IT pioneer, businesswoman and philanthropist who has campaigned for equal treatment for women in the workplace. She founded the first all-women IT firm handling projects that included the world’s first supersonic jet airliner - Concorde.

Her life in commercial computing, however, began with the ICT 1301.

Dame Stephanie joined ICT’s Computer Developments Ltd (CDL) subsidiary to work on delivery of the 1301. She was responsible for ensuring the engineers built a computer that worked.

It was a unique challenge: Dame Stephanie was one of just three women in a CDL workforce of 35, reflecting the lack of women in influential technology positions at that time. Aged 26, she held what she called her first “proper” management position - fresh from the Post Office Research Station.

Deadlines to deliver the 1301 were tight. Pressure was coming from UK rivals and IBM, added to which ICT was struggling to meet customer demand.

Against these pressures and amid rising customer expectations, Dame Stephanie devised complex software programs to test the performance and reliability of the 1301’s hardware, architecture and systems. She worked long shifts, often at night, testing the engineers’ output.

The 1301 was a challenge to get right, with its mix of new technologies and capabilities introduced to make the computer faster and more reliable. If her tests failed, so did the 1301.

Dame Stephanie was driven by a love of her job and a belief that the 1301 held great commercial value for Britain. The 1301’s eventual success with customers in big business and government in the UK and overseas is a testament to her dedication and quality of work.

Despite this success Dame Stephanie could not progress at CDL. In management meetings she says she was simply told to keep quiet and excluded from key decisions. She therefore resigned and created her own women-only company - Freelance Programmers. By 2000, the company was valued at almost $3 billion.

In her own words - hear Dame Stephanie’s pioneering 1301 story in our video on this page.

The 1301’s the star!

Computers are commonplace on screen today but the 1301 was a pioneer – read: Fame: The 1301 in film and TV to unearth its cult credentials.

Building for Britain

Read how ICT had to up its game with the 1301 in: Here comes IBM! Competitive pressure - and commercial shocks.

Photo courtesy of Stuart Fyfe

Targeted by terrorists

Discover why a pair of police and Government ICT 1301s were attacked in First computer bombed by terrorists.

The first ICT 1301 - the restored Flossie, at her former home on Buss Farm, Kent - running a demonstration program from Rodney Brown and Roger Holmes.

Fame! The 1301 in film and TV

Not all 1301s that retired were reused like Flossie or broken up. Some ended up in the hands of production designers looking for something suitably eye-catching for use in a fictional spaceship, military base or criminal’s lair.

Of course, its appearance was pure whimsy - the 1301 lacked anything like the computing power or sophistication imagined by the creatives. It did, however, convey a sense of power and epitomise “the future”.

The 1301 certainly had on-screen presence: a solid steel chassis housing thousands of germanium transistors, it weighed nearly six tons and filled 65 square metres (700 square feet) of floor space. Its relatively meagre memory and processing power didn’t matter - it was what was on the outside that counted.

A polished grey, chrome and aluminum-coloured case; magnetic tape reels that lurched sporadically inside their retro phone-box-like cases; a huge operator’s terminal full of switches, dials and lights aligned with military precision and a white-noise symphony of clicking, clacking, humming, drumming, whining and whirring. It was this panel that was the star turn, featuring in two James Bond films - controlling solar-power generation in Scaramanga’s base in the Man with the Golden Gun then on the St. Georges spy ship in 1981’s For Your Eyes Only - and in one Pink Panther film as part of Dreyfus’s doomsday machine in The Pink Panther Strikes Again. The 1301 was a favourite of BBC props masters showing up in the second episode of cult favourite Blake’s 7 as well as eight Doctor Who stories in alien ships, on submarines and posing as sinister supercomputers waiting to destroy the universe. Bizarrely, the 1301 also made a cameo appearance in a musical routine by US actress Loretta Switt in an episode of The Muppets and as a humble security system in Hammer Films’ The Satanic Rites of Dracula.

Discover more with our events - checkout the calendar for details

Rare footage of an ICT 1301 with staff at the Peterborough revenue office of the nation’s former train operator - artfully captured in the last quarter of this 8mm film by employee S.E. Gosling.

Targeted by terrorists

On 22 May 1971 a bomb exploded at the Metropolitan Police (the Met) headquarters in Tintagel House, London. It was a time of political unrest in the UK and Europe, but the targets this time weren’t police officers: the intended victims were a pair of 1301s operated by the Met and Home Office.

Why?

Impressed by the 1301’s incredible data-processing capabilities and reassured by its uptake in national and local government, the Met and Home Office bought their computers and shared resources and facilities at Tintagel House.

By today’s standards, Tintagel House was an incredibly exposed facility: the computers were installed on the ground floor with an external, windowed wall accessible to the public. The bomb, placed on an outside ledge, vapourised the window and showered room and computers with dust and debris. Nobody was hurt as the attack took place at night and the room was not staffed. Both machines suffered blast damage but only one stopped and needed repair, a fact attributed to their rugged construction.

Responsibility for the attack came via a statement to the media: “We are destroying the long tentacles of the oppressive State machine… secret files in the universities, work studies in the factories, census studies at home, social security files, passports, work, insurance cards. Bureaucracy and technology used against the people…”

It was Communique 9 from The Angry Brigade - considered mainland Britain’s first terrorist group. The broadly anti-capitalist and anti-establishment Brigade would claim responsibility for 10 bombs in Britain between 1970 and 1971, hitting targets that included cabinet ministers, senior police chiefs, car showrooms and a fashionable London boutique.

The 1301s had been targeted in the mistaken belief that the Met and Home Office were using them to solve crimes. It was pure science fiction: the computers were being used to crunch crime statistics. Two months after the bomb eight people were arrested in London in connection with the Angry Brigade campaign. Four were eventually convicted.

Follow us on Twitter: @tnmoc